Fantastic Entrepreneurs in Japan: Ousuke's Balancing Act of Venture and Tradition

Some entrepreneurs build from scratch. Others inherit legacies. A rare few strive to do both at once.

In Kyoto, a city known around the world for its craftsmanship tradition, I met Ousuke Kambayashi, the third-generation leader of SHOBIEN KYOTO (https://www.norenya.jp), a studio renowned for its mastery of Roketsu dyeing. In other words, an entrepreneur who is reimagining his family’s 60-year-old craft business for the 21st century.

Our paths first crossed in a wonderfully unexpected way. Last year, I spent two days advising founders at Knowledge Capital in Osaka. One prospective founder, born and raised in Kyoto, told me about a friend of his. “He’s the right person to really change the environment of crafts production in Kyoto,” he said, and asked if he could introduce us.

I said yes, of course. The next day, this message landed in my inbox:

“I’m Ousuke, studying business at Ritsumeikan University. I’m trying to figure out how to bring Japanese traditional crafts as luxury items to the world. I focus on expanding my family business and traditional technique called Roketsu dyeing now. I am happy to connect with you and get inspiration from you!”

This is a short story about continuity and reinvention, and about the growing value of human touch in an increasingly abstract world. It also reflects a broader question that I think many people in Japan are quietly grappling with: how to do something new without losing something old.

Human Touch, Enduring Process

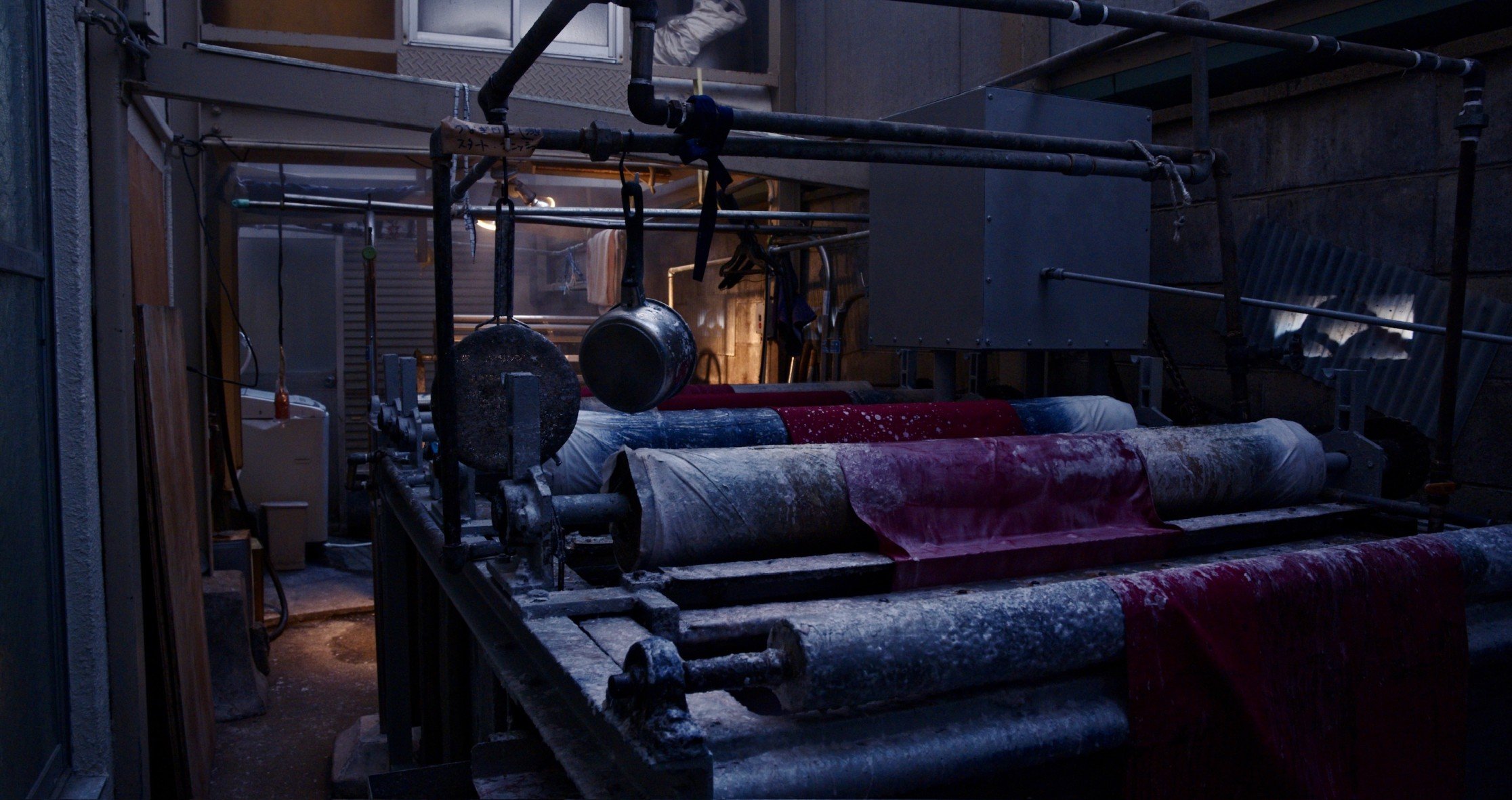

Let us quickly introduce our second main character in this story: the Roketsu dyeing process. And yes, I did ask Ousuke to double check that I got this right: The process begins with white fabric, dipped into a mixture of rice starch and water (a natural primer). Then comes the wax. Using tools passed down through generations, artisans apply patterns by hand. The fabric is then dyed using natural pigments and dyes (indigo, chestnut, and others) each layer revealing subtle tonalities as it interacts with the wax. Finally, the wax is removed in a boiling bath, leaving behind crisp, complex patterns that could never be mass-produced.

From Grandson to Entrepreneur

Ousuke grew up with such wax on his hands.

Born and raised in Kyoto, he spent many of his childhood days running around his family’s dyeing workshop, SHOBIEN. The business was founded by his grandfather in 1963, who moved from Shiga to Kyoto to learn the delicate art of Roketsu-zome. For decades, SHOBIEN became a quiet but respected name in Kyoto’s textile world, crafting fabric dividers known as noren, used in shops, restaurants, and homes throughout Japan.

As a child, Ousuke didn’t think of SHOBIEN as a business. It was simply part of his world, a place where he and his cousin would play while the adults worked. The hum of activity, the smell of wax, the quiet patience of the artisans. All of it settled into his bones, even if he didn’t yet understand what it meant.

The turning point came when he was fifteen. His grandfather was featured on national television, and suddenly the man he’d always known simply as "Grandpa" appeared on screen as a CEO.

"Before that, he was just 'Grandpa.' But suddenly he was a CEO on national television. I realized he was doing something special. I wanted to be like him."

By seventeen, Ousuke had launched a small vintage clothing business. He sourced clothes from Thailand, Korea, and Japan, and resold them online through platforms like Mercari.

"My best month brought in around 2,000 USD, which is a lot for a high school student. More than the money, though, I learned the basics: how to understand customers, how to sell, how to position a product."

Discovering the Startup World

At Ritsumeikan University, Ousuke chose not just a degree, but a new path:

"I joined startup events, met founders, investors, mentors. I became part of Venture Café Tokyo and started building pitch decks for ideas I had around traditional crafts."

He also played an active role in helping shape the local student entrepreneur ecosystem in Kyoto, contributing to early events and workshops at Kyoto Makers Garage and working with other young founders to explore what it would mean to build globally relevant companies from Japan.

He was surrounded by excitement, by people building and breaking things. Yet, something inside him felt out of sync.

"I was making presentations about my family's business, but I hadn't even worked there properly. The artisans didn’t trust me. Why would they? I was just talking."

As Ousuke tells me this, I am reminded of another entrepreneur, Tatsuki Nakata, whom we met earlier this year. As you remember, Tatsuki said:

“My grandfather, a farmer, wasn’t impressed when I told him about the Panasonic job. He said, ‘You’ve never even touched the soil. How can you work in agriculture?’ That hit me hard.”

This strong desire, perhaps instinct, to understand things, for real, through first hand experience, before you build, might very well be a big reason for why Japanese entrepreneurs are building such fantastic products... And, perhaps, it is also part of the reason why it is taking time for Japan's startup ecosystem to grow. A dual edged sword. But, potentially, a huge advantage and opportunity.

So, just like how Tatsuki turned down the Panasonic job to instead gain direct experience from working with farmers, Ousuke stopped:

"I realized I needed to go back to the factory. To understand how it really worked."

He joined SHOBIEN full-time. He did the marketing, managed operations, learned the production process. And through that, he began to understand not just the business, but the culture that surrounded it. Finally, his path was clear:

"Japan is a wonderful country. But if we stay only in Japan, we won't survive the next hundred years."

A Journey to Silicon Valley

With that in mind, Ousuke packed his bags for California. He enrolled at Draper University in San Francisco, a startup training ground for founders and innovators. He also took on an internship to better understand how venture investors think. What struck him immediately was the mindset.

"In Japan, we often try to avoid risk, especially in older industries. But in Silicon Valley, taking risk is part of the game. If you’re not taking risk, you’re not growing."

He also noticed something else, that gave him a sense that he was on the right path:

"Many of the strongest founders were domain experts. They had PhDs, or deep field experience. They weren’t building startups just to build startups. They were solving problems they deeply understood."

The experience left a mark. It validated something he had sensed all along: great businesses don’t come from hype. They come from knowledge. Knowledge, and the courage to take some risk.

Reinventing SHOBIEN: From Noren to Wallpaper

Back in Kyoto, with new-found perspective, Ousuke looked at SHOBIEN with fresh eyes.

"Our core is not noren," he said. "Our core is the philosophy. The method. The craft."

He began to ask new questions. What else could be made with their technique? What other markets might value human-made textures and natural dyes? Then, one customer asked: Could this fabric be turned into wallpaper?

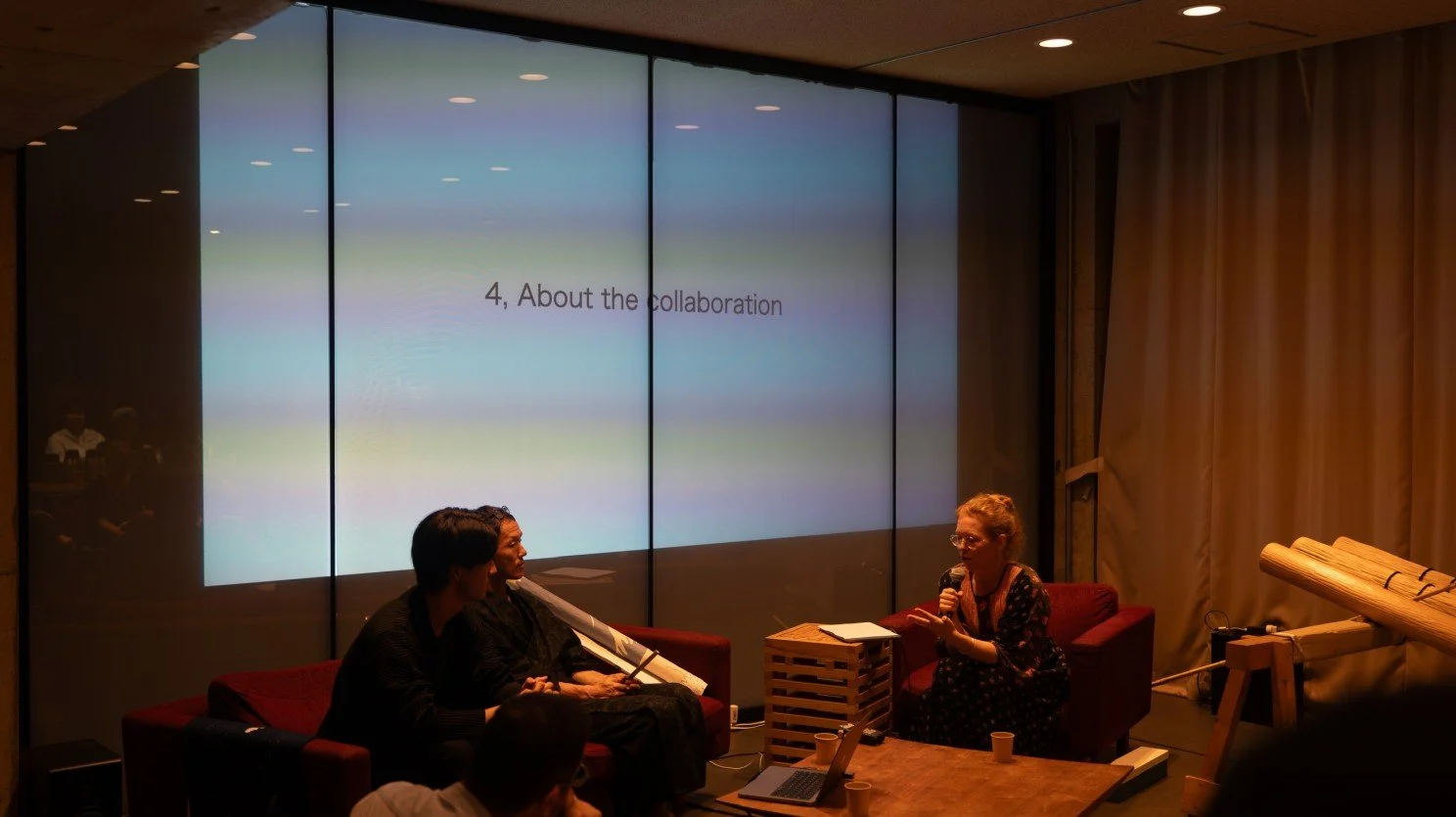

"I hadn't thought about it," he admits. "But I looked around. I found a fourth-generation wallpaper maker in Kyoto. We had the same mindset. We teamed up."

The result: a new business line. The first customer order led to more inquiries. The product began to take shape.

"If one person wants this, maybe ten people do. And if ten do, maybe a hundred do — especially globally."

Seeing their textiles used in modern international spaces (hotels, lounges, boutiques) gave Ousuke a fresh sense of purpose.

"Suddenly I realized: this texture, this color, it belongs not just in Kyoto. It has value anywhere."

Craft, Scaled Through Philosophy

SHOBIEN is now venturing into luxury interior design and fashion textiles. The markets are bigger. The stakes are higher. But the approach stays the same.

"We’re not doing mass production. We never will. That’s not who we are. What we do is humanistic craft. It comes from people. From touch, intuition, and experience."

That philosophy means finding partners who value process as much as product. The wallpaper maker is one. Others are beginning to take notice too: interior designers, boutique hotel owners, and even textile researchers. Technology is not excluded from the picture. Ousuke uses automation in daily operations; for branding, marketing, and scheduling. But the core of SHOBIEN's value remains deeply analog.

"AI helps me work faster. But it doesn’t touch the product. That comes from hands."

Listening as a Growth Strategy

Much of SHOBIEN’s recent expansion has come not from strategy decks, but from conversations.

"A customer says, 'Can you make this into a cushion?' Or 'Could this be a textile for a hotel?' I say, why not? That’s how the wallpaper business started. Just from one person’s curiosity."

His approach to growth is humble and iterative: with a quality product at the core, he is, step by step, adding more risk, and more opportunity, to the equation.

"If a few people want it, there’s probably a reason. And if we can serve that reason well, others will come."

Carrying Culture Forward

Despite his modern outlook, Ousuke remains grounded in Japan’s deeper rhythms.

"In the U.S., people were amazed we’d been around 60 years. That’s a long time there. But here, we’re still young. It made me realize how much value Japan holds."

He sees SHOBIEN’s job as both preserving and translating culture: keeping the meaning alive, even if the form changes.

"Some of our partner companies are shutting down. They didn’t change. And that’s sad. We have to evolve. But that doesn’t mean abandoning what makes us special."

Advice to the Next Generation

For those inheriting family businesses, Ousuke offers simple, hard-earned advice.

"Don’t try to change anything until you truly understand it. Become an expert. Work. Listen. Learn."

He believes respect must be earned both from the past and the present. Without that, change becomes shallow.

"When you know something deeply, then you can start to see what’s possible. Then be brave. Follow the conversations. If people are asking for something, maybe that’s the path forward."

He pauses, then adds: "Culture is something you carry forward — not something you freeze in time."

Closing Thoughts

Learning to cherish the past, and embrace the future, in order to live in the present, is something we could all benefit from. In a time when technology seems to overtake everything, Ousuke's work reminds us that not everything valuable can be digitized. His version of innovation is not about disruption. It’s about continuity. Preserving the spirit of something old, and letting it find new life.

In doing so, he offers hints of a blueprint for how traditional businesses can evolve without losing themselves — and how culture can be a source of growth, not resistance to it. Knowing Ousuke, I believe he would love to talk to other entrepreneurs who find themselves facing similar challenges, to exchange advice, energy, and explore ways to collaborate.

And, speaking of collaboration: Ousuke is extremely driven, and excited to embark on more collaborations with brands and business outside of Japan who are interested in exploring how Japanese craftsmanship can be leveraged to create world-class experiences. I highly encourage you to reach out directly to Ousuke here on LinkedIn: Ousuke Kambayashi.

To learn more about SHOBIEN KYOTO, I warmly invite you all to visit their website https://www.norenya.jp, or follow SHOBIEN on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/shobien_kyoto/.

Until next time,

Tobias